The Maronites, an Eastern rite Catholic Church, profess the same Apostolic Faith, celebrate the same Mysteries (Sacraments) and are united with the chief Shepherd of the Church, the Pope, as all Roman Catholics throughout the world. They have their own distinct theology, spirituality, liturgy and code of canon law.

The Maronites began in the Near East in an area known as the Fertile Crescent, which today comprises the countries of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel. Their common language was Aramaic, the same language spoken by our Lord Jesus Christ in the holy Family at Nazareth, as well as at the Last Supper. Aramaic is still used by the Maronites in various hymns and parts of the Mass, especially at the Consecration.

Of all the Eastern rite Churches, the Maronite Church is the only one known by the name of a person—St. Maroun (also spelled St. Maron).

Born in the middle of the fourth century, St. Maron was a hermit, who, by his holiness and the miracles he worked, attracted many followers. After his death around the year 410, his monastic disciples built a large monastery in his honor, from which other monasteries were founded.

The followers of St. Maron, both monks and laity, were always faithful to the teaching of the Pope. The Maronite Church is the only one among the Eastern Churches that has always maintained its bonds with Rome and the Successor of St. Peter.

The Maronite liturgy is very simple and very rich. The prayers which are used display a profound scriptural tradition, expressing innumerable images and motifs from the Old and New Testaments. The Divine Liturgy of the Mass traces its roots to Antioch, where “the disciples were first called Christians” (Acts 11:26). St. Peter fled to Antioch when a persecution broke out in Jerusalem, resulting in the martyrdom of St. James (cf. Acts 12). According to tradition, St. Peter founded the Church at Antioch and became its first bishop (cf. Eusebius, History of the Church, III, 36). The early Maronites were the direct descendants of the people who received their faith from the Apostle Peter.

The overall characteristic of this liturgical tradition is a strong Trinitarian expression, coupled with emphasis on Jesus Christ as true God and true Man. The Maronite liturgy also retains certain aspects of the ancient liturgy of the Old Testament. For example, at the Consecration, the priest tips the chalice in the four directions of the compass to symbolize the shedding of Christ’s blood for the entire universe, which recalls the practice of sprinkling the four corners of the altar with the blood of the sacrificial lamb.

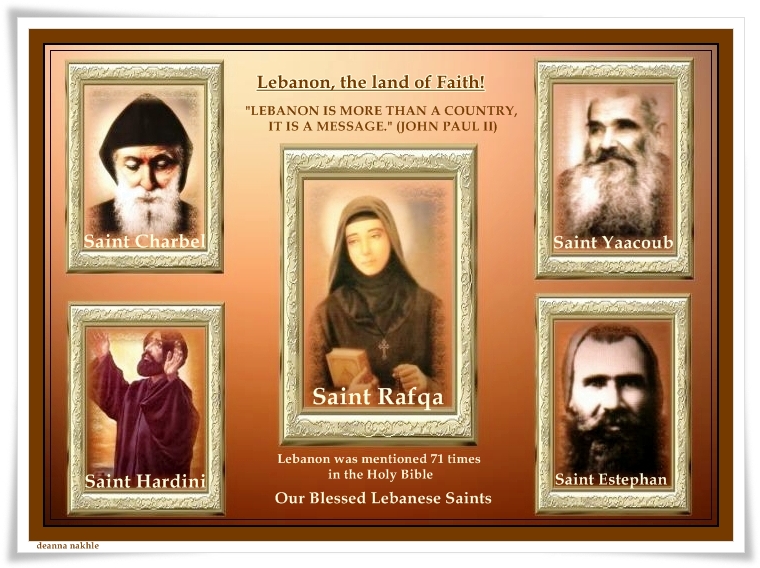

From this ancient and rich spirituality, which cultivates a living spirit of adoration for the Eucharist, many saints have been raised up from among the Maronites. In recent times, three outstanding examples of holiness have been proclaimed by the Church as models for all people of our day: Saint Rafka alReyes, Saint Charbel Makhlouf and St. Nimatullah Al-Hardini .

Saint Rafka was born in the small village of Himlaya on the mountain slopes of Lebanon in 1832. At the age of 21, she entered an order of sisters which later dissolved in 1871. In that same year, she entered the Lebanese Maronite Order. For the next 26 years she lived and worked at the Convent of St. Simon.

Saint Rafka was born in the small village of Himlaya on the mountain slopes of Lebanon in 1832. At the age of 21, she entered an order of sisters which later dissolved in 1871. In that same year, she entered the Lebanese Maronite Order. For the next 26 years she lived and worked at the Convent of St. Simon.

On the feast of the Holy Rosary 1885, Rafka prayed to our Lord that He might allow her to share in the suffering of his crucifixion. From that night on, her health began to deteriorate and soon she became blind and crippled, yet she rejoiced in being made worthy to participate in the suffering of our Lord. After years of acute pain, she died on March 23, 1914 at the Convent of St. Joseph in Lebanon, and since then, many miracles have been attributed to her intercession. In 1985, Pope John Paul II raised her to the honor of the altar, proclaiming her “Blessed” and in 2000 she was canonized a “Saint.” May her prayer be with us.

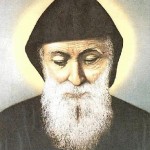

Saint Charbel was born in 1828. He entered St. Maron Monastery in Lebanon in 1853 and lived there as a monk and priest for 16 years. Then, hearing the call of God to a life of greater solitude and prayer, he was given permission to become a hermit. For the next 23 years he gave himself in total dedication to God and the Church in his hermitage by a life rooted in the Scriptures, love for the Eucharist and the Mother of God.

Saint Charbel was born in 1828. He entered St. Maron Monastery in Lebanon in 1853 and lived there as a monk and priest for 16 years. Then, hearing the call of God to a life of greater solitude and prayer, he was given permission to become a hermit. For the next 23 years he gave himself in total dedication to God and the Church in his hermitage by a life rooted in the Scriptures, love for the Eucharist and the Mother of God.

After living a holy life hidden in Christ, he died on December 24, 1898. On the evening of his funeral, his superior wrote: “Because of what he will do after his death, I need not talk about his behavior.” A few months later, a bright light was seen surrounding his tomb. The superiors ordered the tomb to be opened, and they found his body perfectly preserved. Scientific experts and doctors are unable to explain this. Since his death, thousands of re-corded miracles have been attributed to his intercession—so many, in fact, that he is known as the “Wonderworker of the East.”

In  1965, at the close of the Second Vatican Council, Pope Paul VI declared: “ … a hermit of the Lebanese mountain is inscribed in the number of the blessed … a new eminent member of monastic sanctity is enriching, by his example and his intercession, the entire Christian people… May he make us understand, in a world largely fascinated by wealth and comfort, the paramount value of poverty, penance and asceticism, to liberate the soul in its ascent to God.” On October 9, 1977, Pope Paul canonized St. Sharbel at the World Synod of Bishops. May he intercede with God for us.

1965, at the close of the Second Vatican Council, Pope Paul VI declared: “ … a hermit of the Lebanese mountain is inscribed in the number of the blessed … a new eminent member of monastic sanctity is enriching, by his example and his intercession, the entire Christian people… May he make us understand, in a world largely fascinated by wealth and comfort, the paramount value of poverty, penance and asceticism, to liberate the soul in its ascent to God.” On October 9, 1977, Pope Paul canonized St. Sharbel at the World Synod of Bishops. May he intercede with God for us.

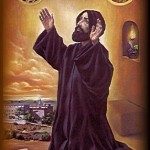

On May 16th 2004, the Maronite Church was again covered in glory as one of her sons, the Blessed Nimatullah Al-Hardini, was raised to the altars at St. Peter’s Basilica, in Rome, by His Holiness Pope John Paul II. The Holy Father had previously declared Fr. Nimatullah venerable in 1989, and elevated him to the rank of Blessed in 1998.

St. Nimatullah Al-Hardini (1808-1858), whose baptismal name was Joseph, was a Maronite priest and religious, and lived a life of heroic virtue in Lebanon where he passed most of his years in monastic solitude. Although shouldering heavy duties of administration, teaching and manual labor (St. Nimatullah practiced his craft of bookbinding even while serving as Assistant General of the Lebanese Maronite Order), the saint maintained an intense spiritual and devotional life including heavy bodily mortifications. He taught at various schools of the Lebanese Maronite Order and among his students was Brother Sharbel Makhlouf—the illustrious St. Sharbel. Along with Sts. Rafka and Sharbel, St. Nimatullah was outstandingly devoted to the Blessed Sacrament, kneeling, sometimes for hours-on-end, in adoration. The Maronite Church celebrates his feast day on the 14th of December.